- Home

- Member Resources

- Pathology Case Challenge

- T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-LBLL)

Clinical Summary

A 14-year-old boy presents to the emergency department with new onset of shortness of breath and easy bruising. On further questioning, his parents report a two-week history of fatigue, abdominal discomfort, nausea, and occasional vomiting. A chest x-ray reveals a large anterior mediastinal mass. The table below lists the results of laboratory testing:

| Test | Result | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| WBC | 145.0 x 109/L | 4.8-10.8 x 109/L |

| RBC | 1.89 x 1012/L | 4.7-6.1 x 1012/L |

| HGB | 5.2 g/dL | 14-18 g/dL |

| HCT | 15.9% | 42%-52% |

| MCV | 84 fL | 80-94 fL |

| MCHC | 32.7 g/dL | 33-37 g/dL |

| RDW | 17% | 11%-14% |

| PLT | 13 x 109/L | 150-450 x 109/L |

| LDH | 462 U/L | 110-283 U/L |

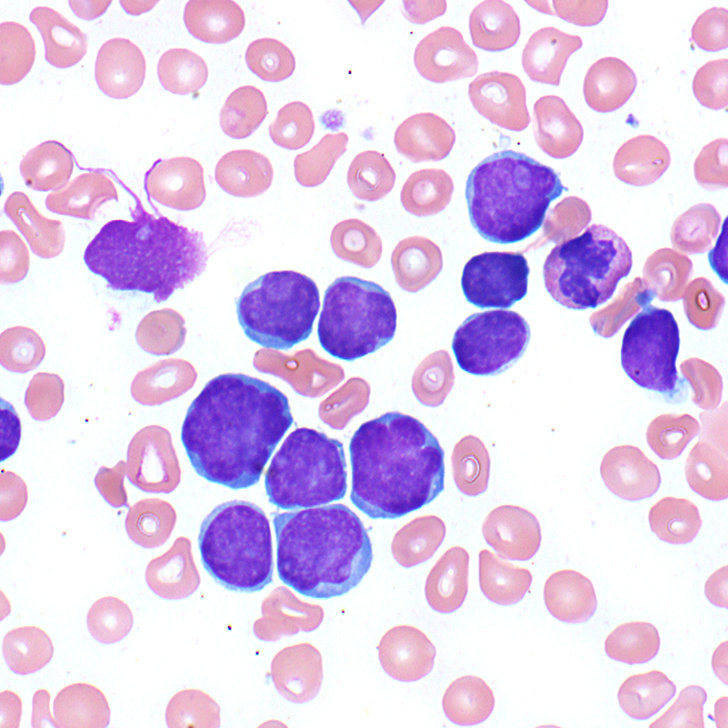

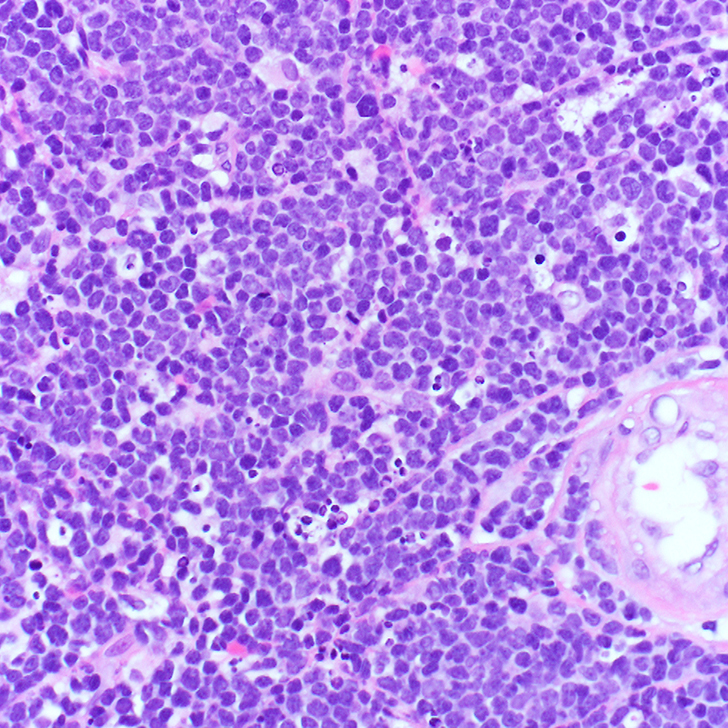

The patient’s peripheral blood smear shows the presence of abnormal cells (Figure 1A), which are morphologically similar to those seen in image-guided biopsy of the mediastinal mass (Figure 1B).

Master List of Diagnoses

- T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-LBLL)

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Thymoma

- Germ cell tumor

Archive Case and Diagnosis

This material was originally released as the 2015 CPIP-G Case 07: Molecular: T- Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma (SAM eligible).

Criteria for Diagnosis and Comments

The differential diagnoses of a mediastinal mass in a young patient include lymphoma (such as lymphoblastic, Hodgkin, primary mediastinal large B-cell), germ cell tumor, and thymoma. The presence of a large mediastinal mass with marked leukocytosis with abnormal cells (blasts) makes T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (T-LBLL) the most likely diagnosis.

The CBC shows marked leukocytosis with marked normocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. The peripheral blood smear shows numerous lymphoblasts characterized by scant pale cytoplasm, irregular nuclear contours, and variably-dispersed chromatin with mostly inconspicuous nucleoli (Figure 1A).

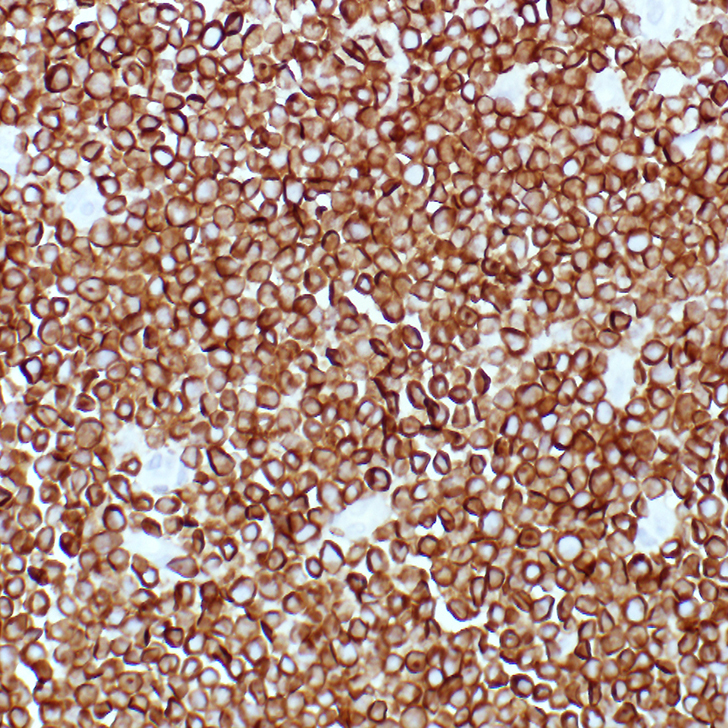

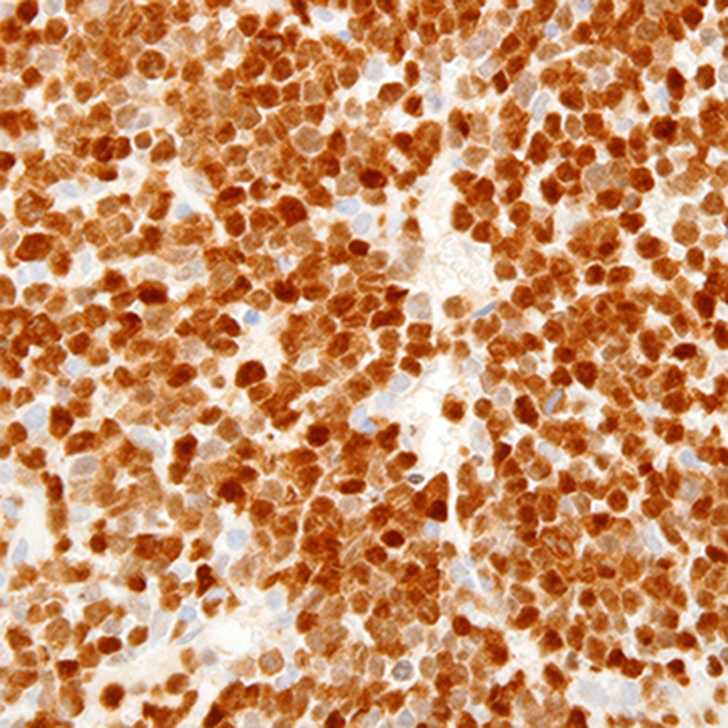

The mediastinal mass tissue specimen shows diffuse infiltration by sheets of small and medium-sized immature cells (Figure 1B). The neoplastic cells express T-cell antigens, including cytoplasmic CD3 (Figure 1C) and markers of immaturity, such as nuclear terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) (Figure 1D). These morphologic and immunophenotypic findings are diagnostic of T-LBLL.

T-LBLL is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell neoplasm of lymphoid precursors (lymphoblasts) that are committed to the T-cell lineage. Nearly 90% of T-LBLL tumors are extramedullary.

The clinical presentation of T-LBLL is variable. Although most patients present with acute onset disease, the initial symptoms and signs may be insidious and are slowly progressive over weeks or months. The presenting clinical signs depend on the degree of bone marrow involvement and extent of extranodal disease. Blood cytopenia’s and fever are frequently present. In cases with very high white blood cell counts (WBCs), central nervous system (CNS) involvement is frequent. Less common signs include headache, vomiting, and respiratory distress. Life-threatening infections and bleeding may also occur due to cytopenia’s resulting from bone marrow infiltration by the tumor cells.

Most T-LBLLs arise in the thymus, which is the anatomic site of normal T-cell development and will present as a mediastinal mass. Such cases may manifest with a pleural effusion and, less frequently, a pericardial effusion. T-LBLL is not restricted to the mediastinum and can also involve any lymph node or extranodal sites such as skin, tonsil, liver, spleen, CNS, and testes in males.

When leukemia is the predominant manifestation anemia, thrombocytopenia, and relative or absolute neutropenia are frequent. Blast counts may vary from rare blasts to very high numbers of blasts. The T-lymphoblasts vary from more typical small lymphoblasts with variably-condensed nuclear chromatin, absent nucleoli, and almost no cytoplasm to large cells with finely-dispersed chromatin, conspicuous nucleoli, and moderate amount of cytoplasm (Figure 1A). T-lymphoblasts also tend to have more pronounced nuclear convolutions and more basophilic cytoplasm.

Immunophenotyping is essential for lineage determination in patients with newly-diagnosed T-LBLL. This is usually accomplished by flow cytometry (Figure 2) performed on diagnostic tissue, peripheral blood, or bone marrow specimens.

In some instances of T-LBLL without medullary or bone marrow involvement, a specimen may not be available for flow cytometry evaluation. IHC allows for an alternative method of immunophenotyping in these situations. The T-lineage lymphoblasts of T-LBLL typically express normal T-cell antigens including CD2, cytoplasmic CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, and CD8. Of these, only cytoplasmic CD3 is considered lineage-specific as a T-cell antigen by current World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines.

Surface CD3 expression, typical of mature T-cells, is often absent or variable/weakly expressed. Nuclear terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) is positive in more than 90% of cases and helps to establish immunophenotypic evidence of cellular immaturity. Expression of CD1a, CD34, and CD10 (also indicators of lymphoblast immaturity) are variable.

T-LBLL is not currently subclassified according to recurrent genetic findings. However, an abnormal karyotype is found in the majority of cases and genetic studies have provided significant insight into the underlying biology of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). The most frequent nonrandom cytogenetic abnormalities seen in T-ALL are translocations that involve T-cell receptor (TCR) loci on chromosomes 7 (TCR alpha and delta) and 14 (TCR beta and gamma) in association with various partner genes such as LMO1, LMO2, TAL1, TLX1, and HOXA. Many of these rearrangements involve dysregulation of cellular and T-cell specific transcription factors, resulting in disruption of normal maturation or uncontrolled cellular proliferation, suggesting a role in leukemia pathogenesis. In addition, TLX1 gene rearrangements and NOTCH1 activating mutation have been reported in T-LBLL and appear to be associated with favorable outcome. Their role as a diagnostic tool or a therapeutic target has not been established. T-ALL in childhood is generally considered a higher-risk disease and is associated with a higher risk of induction failure, early relapse, and isolated CNS relapse. Minimal residual disease following therapy is a strong adverse prognostic factor.

In summary, T-LBLL is a clonal hematopoietic stem cell neoplasm of lymphoid precursors (lymphoblasts) that are committed to the T-cell lineage.

- Nearly 90% of T-lymphoblastic tumors are extramedullary lymphomas and should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of mediastinal tumors, particularly in pediatric, adolescent, and young adult patients.

- Morphologic evaluation in conjunction with immunophenotyping, preferably by flow cytometry or alternatively by IHC, is required for definitive diagnosis.

- The lymphoblasts of T-LBLL typically express T-cell antigens including cytoplasmic CD3, which is considered lineage-specific T-cell antigen by current WHO guidelines. Nuclear TdT is positive in more than 90% of cases and helps to establish immunophenotypic evidence of cellular immaturity.

T-LBLLs are aggressive but generally curable malignancies that require immediate diagnosis and proper treatment. Response to therapy and presence of residual leukemia (eg, MRD) appear to be the most important prognostic factors.

Supplementary Questions

- Presence of mediastinal mass and blasts on peripheral blood smear in a 5-year-old child is highly suspicious of:

- Thymoma

- Hodgkin lymphoma

- Germ cell tumor

- T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia

- A common cytogenetic abnormality associated with T-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma is:

- t (9,22)

- 3p deletion

- translocation involving TCR (T-cell receptor) on chromosome 7 & 14

- t (8,14)

References

- Borowitz MJ, Chan JKC. T lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008.

- Kjeldsberg CR, Perkins SL, eds. Practical Diagnosis of Hematologic Disorders. 5th ed. Singapore: American Society for Clinical Pathology; 2010.

- Coustan-Smith E, Mullighan CG, Onciu M, et al. Early T-cell precursor leukaemia: a subtype of very high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2009 Feb;10(2):147-56.

- Zhang J, Ding L, Holmfeldt L, et al. The genetic basis of early T-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2012 Jan 11;481(7380):157-63.

- Hoelzer D, Gokbuget N. T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a separate entity? Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2009;9(Suppl 3):S214-21.

- Kraszewska MD, Dawidowska M, Szczepański T, Witt M. T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: recent molecular biology findings. Br J Haematol. 2012;156:303-15.

Authors

Maria A. Proytcheva, MD, FCAP

Jay L. Patel, MD, FCAP

Excerpted for Case of the Month by:

Vandita Johari, MD, FCAP

Vice Chair Clinical Laboratory Affairs, Department of Pathology, Baystate Health

Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, UMMS-Baystate

Answer Key

- T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (d)

- translocation involving TCR (T-cell receptor) on chromosome 7 & 14 (c)